North Walsham in the 19th Century

Index.

- FOREWORD

- THE LATEST FASHIONS

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 1 - North Walsham mid 19th Century

- Chapter 2 - A Young Society

- Chapter 3 - The North Walsham and Dilham Canal

- Chapter 4 - Bluebell and Spa Commons

- Chapter 5 - Assisting the poor

- Chapter 6 - Poverty & Protest: The Agricultural La

- Chapter 7 - Crime and Punishment

- Chapter 8 - The Fisher Theatre

- Chapter 9 - North Walsham Celebrations

- Chapter 10 - The Impact of Religion

- Chapter 11 - Education in North Walsham

- Chapter 12 - The Railway come to North Walsham

Extract from "North Walsham in the nineteenth century"

The Historical Research Group of the North Walsham W.E.A.

Edited by Pam Warren.

Chapter 1

THE TOWN IN THE MID 19th CENTURY:

TRADES AND OCCUPATIONS, SHOPS AND SHOPPING.

The principal source for this study is the 1851 Census Return for North Walsham, complemented by a number of Directories covering the Norfolk area. The first Census was in 1801 and since that date it has been conducted every decade except for 1941 although the earlier Returns contain less information. The Census of 1811 and 1821 for North Walsham were carried out by a local solicitor, James Legood, who received the princely sum of a halfpenny for every name entered. Only the name of the head of the household was entered at these dates, whether he, or she, was engaged in trade or agriculture, or neither, together with the number of males and females in the household. Very few of the streets in the town are indicated.

It is from 1851 that the Census becomes much more detailed. Special officials, usually local men, were appointed as enumerators. North Walsham was divided into five districts, with one officer for each district to visit and record the details of each household. Every member of the household was listed by name, marital status, age and place of birth together with occupation and relationship to the head of the household. The name of the street is entered against each household, but not the number of the property so that identification is not easy, even where dwellings are still in existence today. The information is what the Census Official has been given and so the description of occupations, for example, could differ although they may, in fact, have been the same.

North Walsham had a population of 2,911 in 1851. Although the town is generally considered mainly as a small market town the importance of agriculture is revealed by the Census Return. Agricultural labourers formed, by far, the largest occupational group, numbering about 230. Boys as young as 9 years old were working on the land, although this was exceptional. There were 36 farmers, working from four to 700 acres of land and a number of men was employed in trades and occupations connected directly or indirectly with agriculture such as blacksmiths, saddlers, wheelwrights, carriage and gig-makers, curriers, millers, etc. One of the many blacksmiths was a William Shipley at Whitehorse Common. He was also a veterinary surgeon, as blacksmiths sometimes were in the past. His son moved to Great Yarmouth and established a flourishing veterinary practice there.

It is not surprising that the building industry comprised a fairly large group as the town had expanded considerably during the previous decades; many of the bricks for building in the area would have been made locally. There were sixteen brickmakers and in addition there were labourers employed in the trade. The principal brickmaking site was Brick Kiln Farm at Spa Common - brick kilns at this site were, in fact, recorded in 1826 on Bryant's map of Norfolk. In the middle of the century John Fox and Thomas Amis were master brickmakers there. In addition to supplying local needs Thomas Amis also supplied bricks to Lord Wodehouse, owner of Witton Hall, for use on the Witton Estate.

Small shopkeepers and other tradesmen formed an important group in the life of the town, some of whom are discussed in the following pages. The professional group also formed a small, but significant group essential to a small market town such as solicitors, attorneys, auctioneers and land agents.

Domestic service topped the list of female occupations employing over 150 women and girls. In the Victorian period a servant was essential to the gentry and professional home; moreover, it is found that some small shopkeepers and tradesmen also kept a servant. Most servants were under the age of 30. Some girls entered service at a very early age, although generally girls seemed to stay at school longer than boys. Often boys were found to be working but their sisters, although older, were still at school. Male servants were few in North Walsham in this period, and were generally employed as grooms or handymen amongst the gentry. Perhaps the number of servants employed by the clergy, even by the nonconformist clergy, surprises. They all maintained substantial establishments and several clergy with livings in nearby villages were also domiciled in the town. The vicar of North Walsham, the Rev. William Wilkinson maintained four living-in servants which included one male servant.

The wives and children of the less 'well to do' shopkeepers would have often helped as assistants, but this was by no means always the case, and where there were several children it is found they were sometimes apprenticed to other trades in the town. Whilst Victorian wives of the middle and upper classes may well have led leisured lives this was not so for the wives of those lower down the social scale. In addition to running a home these women needed employment for additional financial support and many would have taken on agricultural work in busy seasons. A number were described in the Census Return as laundress, charwoman and a very popular and, a somewhat socially more acceptable occupation, as a dressmaker. The number of women in this occupation amounted to the high figure of 60 although some, no doubt, worked on a part-time basis. Before mass production few clothes were bought ready-made and there would have been a steady demand from local customers as well as from those from the surrounding area for the latest fashions or for more serviceable wear for the less well off.

It is, perhaps, surprising that a considerable number of people living and working in North Walsham was not born in the town but in the surrounding villages. The growth of population in Norfolk since the earlier part of the century led to insufficient work being available in many rural areas so that many came to the town for work. It would seem that this is the reason for so many lodgers throughout the town since, due to lack of adequate transport, and in a period before the railway and the bicycle, many young people who came to work were forced to lodge in the town itself. Besides two inns which seem to have provided cheap lodgings many small houses lodged two or three people, doubtless to help the family budget as well as fulfilling the need to supply accommodation for the unmarried man or woman working away from their home. In a few cases, paupers were lodged in private houses rather than in the workhouse.

Twenty-five people in the town were described as annuitants in 1851, having money invested to bring in a yearly income. This was a fairly common way of securing a comfortable standard of living in this period, particularly for middle class spinsters. (Modern hyper-inflation has meant that this form of income has become much less attractive). A few were noted as 'owner of property' or 'landed proprietor' although few people in North Walsham owned their own homes; less than half of the shopkeepers in the town owned their own premises and often, if they did, they rented further properties. The vast majority of houses and cottages were rented and rents from properties could secure a fair livelihood. Some farmers, too, rented their farms, although they might be landowners themselves.

North Walsham appears to have been a fairly prosperous small market town in the middle of the century which could supply within itself almost all its own needs. It would also have served small villages in the surrounding countryside. The railway was not to reach the town until 1874 although the town was not isolated: people relied on their own horse-drawn conveyances or public transport supplied by coaches or carriers. There was a daily coach service to Norwich and back apart from Sundays. Carriers also served Norwich three times a week as well as providing regular services within the immediate area. There were two daily services to Mundesley and one to Bacton; Runton and Cromer were served twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays and Yarmouth on Tuesdays and Fridays. Numerous small villages between these places would be called at. Carriers were not only used for transporting goods, poor families would usually journey by the carrier's cart, which was much cheaper than coach transport. Moreover, it is very likely that the North Walsham carriers shopped in the town or delivered messages there for a few pence on behalf of some of their rural customers.

North Walsham appears to have been a fairly prosperous small market town in the middle of the century which could supply within itself almost all its own needs. It would also have served small villages in the surrounding countryside. The railway was not to reach the town until 1874 although the town was not isolated: people relied on their own horse-drawn conveyances or public transport supplied by coaches or carriers. There was a daily coach service to Norwich and back apart from Sundays. Carriers also served Norwich three times a week as well as providing regular services within the immediate area. There were two daily services to Mundesley and one to Bacton; Runton and Cromer were served twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays and Yarmouth on Tuesdays and Fridays. Numerous small villages between these places would be called at. Carriers were not only used for transporting goods, poor families would usually journey by the carrier's cart, which was much cheaper than coach transport. Moreover, it is very likely that the North Walsham carriers shopped in the town or delivered messages there for a few pence on behalf of some of their rural customers.

There were 15 inns and public houses in the town; some offered accommodation and stabling for horses as the town was a convenient stop-over for travellers. In addition, there were six beerhouses. North Walsham, in company with most other places in the kingdom, must appear to have had a very sottish population! For many there was little entertainment apart from the public house and what was provided was usually too expensive for poorer families. Many could neither read nor write, homes were very cramped and the local pub offered evening gossip and escape at the end of a long day's work.

The town must have been particularly busy on market day which was every Thursday. A considerable amount of business was conducted at the new corn hall which opened in 1848. It seems that butter and eggs were sold directly from private houses on these days as well as in the shops and market stalls. As farmers from the surrounding area did business and patronised the local inns no doubt their wives made their way around the town to buy up some of the many things on offer. As they went about the town centre they would have found almost everything required close at hand. There was George Wilier, a shoemaker in the Market Place and Samuel King nearby, who described himself as a cordwainer, (another rather fancy name for the same occupation) employing three men, to supply one's footwear, though there were plenty of others too to choose from about the town with almost 50 men being employed in this particular occupation. Then there were the brothers Steward, the glovers -gloves being a somewhat more important piece of clothing in those times than to-day. Nearby, James Buck would make guns, helped by one apprentice. He had a large family: one son was apprenticed to his father, another was an apprentice cabinet maker, next came a daughter employed as an errand girl and a son employed as a errand boy. There were three younger children described in the Census Return as scholars. A Mrs Richardson supplied straw bonnets, whilst her sister made dresses. There was a Mr. John Riches, a hairdresser, one of three in the town. There was also a farmer bearing the same name who employed 35 men and it was presumably he who paid for the mosaic paving for the Market Cross when it was taken over from the Church Commissioners and repaired by public subscription about this time.

There was a James Wright, linen draper, doubtless a forebear of a name still surviving in the town. Mr Wright advertised himself as a Linen Draper, Silk Mercer, Hosier and Haberdasher. He also mentioned a Carpet Warehouse and advocated "small profits for quick returns." He supplied Irish Linen, Damask and Diaper Table Cloths, Napkins, Ribbons and Lace. Also Counterpanes, Morcella Quilts, Bed Ticks, Bombasins (twilled dress material), Blankets, French Cambrics, Long Lawns (often associated with bishops' sleeves), Fancy Handkerchiefs, Rich Shawls, etc. He also could supply mourning of every description - something which was considered rather more important at that time.

Mr. Woods, who employed two men, made harnesses. In an age prior to the motor car carriages, carts for private and business use and every need for horse-riding and horses would have been provided for within the town and gave considerable employment. Thus, in Bank Street, just by the Market Place, was Mr. Simpson, a saddler and harness-maker, employing one man and two apprentices and like many others in business he was also a farmer on a small scale. Next door, Groom Lane described as a farrier (blacksmith) and currier (leather dresser) employed four men. A John Storey, one of the many tailors about the town, employed three men. Next was George Juler, a watchmaker and silversmith, then Richard Sadler, a druggist and chemist.

The Butchery, an offshoot of the Market Place, contained only a few butchers, Mr. John Dyball, Mr Edward Bailey and Mr. John Hall but there were other shops including that of Thomas Warnes, described exclusively as a Tea Dealer and a William Johnson, who supplied china and earthenware. John Watson, at the Maid's Head, on the day of the census, was supplying accommodation to a somewhat motley crowd which included one traveller, three pedlars and eight beggars! Then there was a Samuel Newton, one of several bakers in the town.

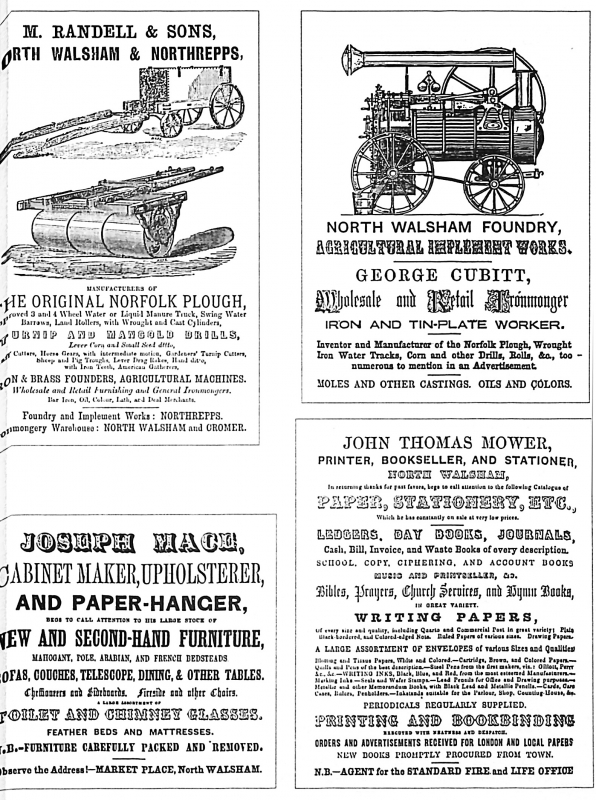

George Cubbitt had The North Walsham Foundry in King's Arms Street. This was eventually taken over by Randells and one, at least, of the Randell family today can claim descent from both the Cubbitts and the Randells. An advertisement in Hunt's 1850 Directory, reproduced here, described George Cubitt as a wholesale and retail ironmonger and the manufacturer of the Norfolk Plough, wrought-iron water tanks, corn and other drills, rolls and other items 'too numerous to mention'. Harrod's 1868 Directory gives an even more expansive list which included steam engines ' of every description', one of which is illustrated in the earlier advertisement. Randells was established in 1820 and they, too, advertised in the Norfolk directories, listing their foundry at Northrepps and an ironmongery warehouse in both North Walsham and Cromer. When James Randell died, the company was taken over by his wife. Later two sons took over as F & H. Randell with the foundry in Bacton Road established about 1870. The Somerfield Supermarket now stands on this site. Horace left the business and it then became known as F. Randell Ltd. Frederick was the great inventor and his successes included a four row steerage hoe for sugar beet and iron wheeled water carts. Within living memory of the present Randell generation there was still, in situ, the large wheel fire engine he specially constructed so that it could be pulled up and down the stairs in the shop in the Market Place.

Among the dozen or so grocers in the town - often a drapery business was conducted on the same premises - the establishment of Mr. Drake Sewell was, perhaps, the largest. He was described as a Grocer, Tea Dealer and Tallow

Chandler. Candles were, of course, an important item in the shopping list in the 1850's. He employed two assistants and three apprentices. There would have been much more work involved in running a small shop in the past in the days before 'self-service' and modern packaging. Tea, sugar and butter and numerous other goods all had to be weighed and packed for each customer.

There is an advertisement by a Mr. E. T. Rowse of the Market Place about this time, but his connection with the town must have been a short one as his name occurs neither on the 1851 census list nor in the White's directories immediately before or after this census. He described himself as 'A Family Grocer, Tea Dealer and Provision Merchant' stating that 'All teas at this Establishment are selected with the greatest care and by a judicious combination of the different properties of each kind, an article is submitted to the public possessing unequalled strength and the finest flavour'.

Whilst today a number of businesses act as agents for insurance companies and building societies, in the mid-nineteenth century a number of shopkeepers acted as agents for fire and life offices. Some businesses covered a surprising number of different activities: William Pope, for instance was not only an auctioneer and appraiser but was also a hatter and postmaster!

A prosperous business in the town was that of Joseph Mace. His advertisement shows he was a 'cabinet maker and upholsterer'. He employed six men and four apprentices in the 1850's. He also described himself as a paper hanger and, as well as selling an assortment of furniture, also did 'removals'. The Mace family had established a furniture business in the town by 1830, and they may. perhaps have been in the town earlier. The shop survived well into the 20th century but this firm had no connection with the firm of builders by the name of Mace. A Mr. Wilson, who lived in Beech Grove, in New Road (the house was later burnt down) had a building business which failed. John and William Mace, who hailed from Cromer and who had been employed by Mr. Wilson took over the business with a loan of £70 from Wilkinson and Davies, the solicitors, now Leathes Prior. This would have been in the 1880's. When John died William carried on alone and the firm of William Mace went from strength to strength, finally being sold some four years ago.

Near to Mace, the cabinet maker, was William Crook, another chemist and druggist. Then there was The Terrace where, among others, was Mr. Richard Baker who managed the East of England Bank, one of three banks in the town, and John Denys, a land agent. Then, back to the Market Place, where there was a Mr. Mower, one of two printers and stationers of which the town could boast; the other was John Plumbley. In an advertisement John Thomas Mower offered paper and stationery at very low prices, also 'ledgers, day books, journals, cash, bill, invoice and waste books of every description'. School. Copy, Ciphering and Account Books are also listed together with Bibles, Prayer, Church Service and Hymn Books. In addition to these and many other things he also sold black lead and metallic pencils and inkstands 'suitable for parlour, shop and counting house'. Next to his premises was The Berlin Wool Repository managed by a Mrs. Pitcher who offered a fine dyed wool, suitable for knitting or tapestry work.

There was a number of other shopkeepers in the streets near The Market Place. Dog Corner had a provision shop and a pork butcher; there was Mr. Pilgrim's beershop and also the Dog Inn, run by William Dunton, with presumably some very cheap lodgings as, like the Maid's Head, it seems to have accommodated some rather dubious customers. On the day of the census, besides William Dunton and his family, a servant and a scholar lodger, there were four rag dealers, three beggars and six pedlars staying there! Pedlars offering various wares and 'rag and bone' men about the countryside were quite common in the past and these men were most likely itinerants passing the night in the town; all but one were born outside Norfolk.

In Chapel Street there was a Mr. Rorfe, a Police Officer, living at Police Station house. He had in his house four prisoners - the O'Brien family from Dublin all described as vagrants. They were probably being held temporarily there whilst waiting to be escorted back to their own parish in Dublin which was responsible for their support.

Sources:-

1811, 1821 Census Returns, Envelope 2, Parish Papers. 1851 Census Returns, N.L.S.L.; Norfolk Directories;

Map North Walsham Market Place, extract from copy (1860) Enclosure Award Map 1814, ref: Church Commissioners 1643080; reproduced by kind permission of the Norfolk Record Office.

Information and assistance is gratefully acknowledged from Mr. H. W. Mace, Mr. A. J. Randell and Mr. R. F. Randell.

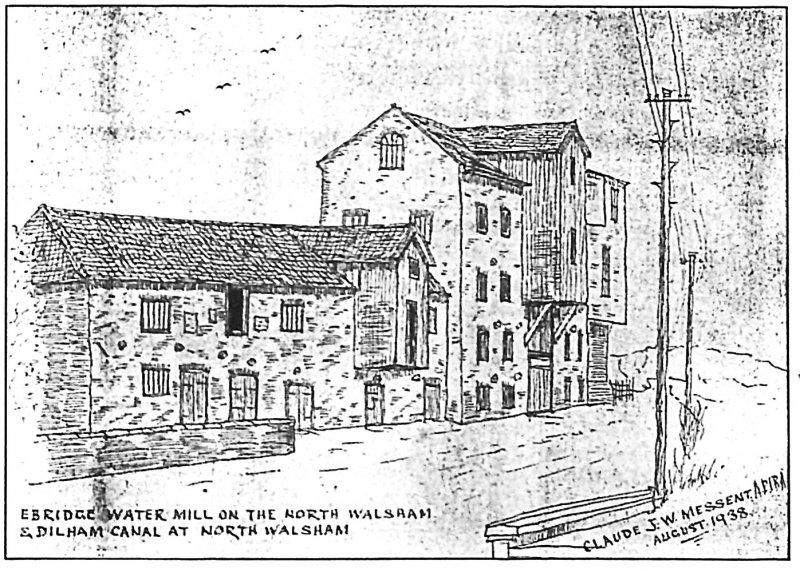

EBRIDGE MILL

The mill has a long history . It was presented to St. Benet's Abbey by Streth the Saxon and it passed to the Bishop of Norwich at the Dissolution. Manor Court Rolls show that during Henry VIII's reign the mill was leased to a William Hogan for £4. 13s. 4d.

The Partridge family had a long connection with the mill, certainly from the late 18th century ( and perhaps earlier) when, in 1793, the lease was held from the Bishop by a William Partridge. The family continued as millers there until the 1860's and in the middle of the century they were employing two men to assist them.

Cubitt and Walker's connection with the mill is even longer. It began over 120 years ago, in 1869, when they purchased the mill from the Bishop. At that time it consisted of little more than a single waterwheel. The mill was expanded and business throve with the canal. Alas, today, it no longer grinds flour - the last bag was produced in 1966 - but supplies large quantities of animal feed, mainly for pigs and poultry, and also lesser amounts for beef and dairy cattle, turkeys and rabbits.

Yarmouth Independent 27 August 1938.

Information and assistance from Mr. Christopher Walker is gratefully acknowledged.